Quiero Agua Video Gore and the Rise of CJNG El Payaso

In the dark and violent underworld of Mexico’s cartel wars, few things have shocked the public as much as the gruesome video now circulating under the name “I Want Water.” This video, widely described as one of the most disturbing cartel execution recordings in recent years, shows the torture and partial mutilation of a man by a cartel hitman known only as “The Clown.”

The victim, whose identity is unofficial but locally acknowledged, has been dubbed “The Mexican Ghost Rider” a reference to the comic book character, owing to the fact that his facial skin was removed while he was still alive. This act of horror was carried out by operatives of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), allegedly under the command of “El Payaso del CJNG,” or “The Clown,” who serves as plaza boss in the embattled region of Aguililla in Michoacán.

This article delves into the individuals involved, the video’s implications, and the broader context of cartel warfare that continues to plague western Mexico.

A Brutal Message Captured on Video

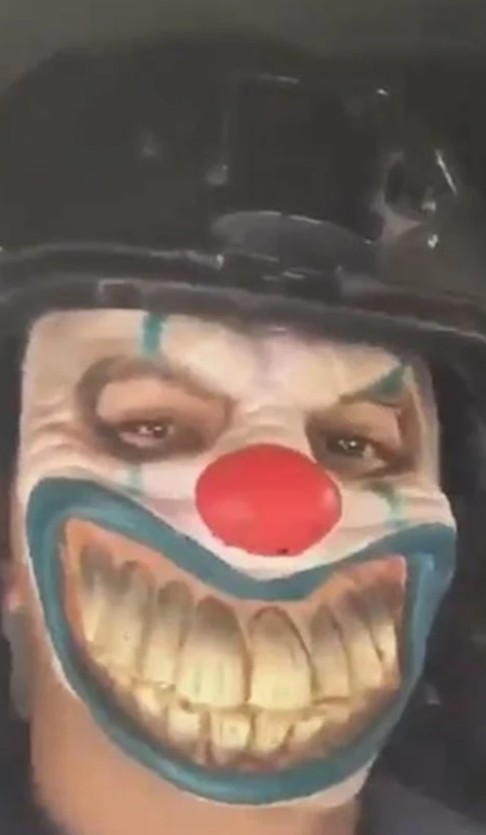

The “I Want Water” video opens with the victim bloody, tied, and clearly tortured uttering the desperate plea for water. Moments later, a man wearing a clown mask or with clown-like makeup begins to carve into the victim’s face with a knife. It is later confirmed through insider sources and narcomessages that the perpetrator is “The Clown,” a notorious CJNG sicario (hitman) who has built a reputation on gruesome executions used for propaganda and intimidation.

The victim’s video makes anyone who watches it cry, those people have no compassion

Although the video does not show the exact moment of death, the severity of the injuries leaves no doubt that the man died shortly after filming. The grotesque image of a flayed face, likely intended to dehumanize the victim and serve as a psychological weapon, has led social media users and locals to label the man “The Mexican Ghost Rider.”

CJNG and the Control of Michoacán

The Jalisco New Generation Cartel, or CJNG, has risen rapidly in the last decade to become one of Mexico’s most dangerous and dominant criminal organizations. Founded by Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, also known as “El Mencho,” the cartel is known for its paramilitary structure, sophisticated weaponry, and horrific violence.

Michoacán, once dominated by rival cartels like La Familia Michoacana and Los Caballeros Templarios, has become a warzone where CJNG seeks to claim control of valuable trafficking routes. Towns like Cotija and Aguililla have turned into battlefronts, with local citizens caught in the crossfire of territorial disputes.

Aguililla, the hometown of El Mencho, has long been considered a strategic stronghold for CJNG. In recent years, the region has seen an uptick in drone attacks, road blockades, and brutal executions all signs of an escalating cartel war.

“The Clown” – CJNG’s Gruesome Face of Fear

While many sicarios operate in relative anonymity, “The Clown” has cultivated infamy for his cruel methods and theatrical presentation. Known in Spanish as “El Payaso del CJNG,” he has allegedly overseen several brutal killings, often leaving behind narcomensajes that contain threats to rivals or taunts to law enforcement.

By assuming the identity of a clown a figure typically associated with humor and childhood he turns innocence into horror. For many in Michoacán, his name has become a symbol of nightmare-inducing brutality.

The use of costumed personas in cartel violence is not unprecedented, but “The Clown” has taken the concept further by turning each killing into a symbolic act of terror. By skinning his victim’s face, he achieved two objectives: instill fear in rivals, and create a grotesque narrative for viral circulation.

The Victim: From Anonymous Man to “The Mexican Ghost Rider”

Very little is officially known about the victim, but sources close to the situation say he was a local man from Cotija, a town increasingly under siege by cartel forces. Whether he had any ties to a rival organization, such as Los Viagras or La Nueva Familia Michoacana, remains unclear.

What is clear, however, is that his death was meant to send a message. His face, peeled from bone while alive, was not just an act of cruelty it was propaganda. By branding him as “The Mexican Ghost Rider,” the internet and local communities gave the faceless man a new, haunting identity.

His plea for water, heard faintly in the video before the attack intensified, has struck a deep emotional chord among viewers adding a layer of tragic humanity to an otherwise horrifying spectacle.

The Message Behind the Mutilation

Cartel videos have long been used as tools for psychological warfare, both within the criminal world and in the public eye. The CJNG in particular is known for broadcasting acts of extreme violence as warnings. These videos function as both deterrents to rivals and as demonstrations of power.

In this case, it is believed that the murder was a direct message to Los Viagras a rival cartel still fighting for dominance in the region. The CJNG frequently leaves narcomensajes near the bodies of their victims, often implicating rivals, accusing them of betrayal, or warning of future consequences.

According to local whispers, the body of the Mexican Ghost Rider is expected to be dumped somewhere in Cotija, along with a message either mocking Los Viagras or threatening escalation.

Retaliation and Fear of Escalation

At this time, there has been no official response from Los Viagras. However, within cartel dynamics, retaliation is almost a certainty. If the victim was perceived as one of their own, they may feel compelled to respond violently. More concerning is the possibility that Los Viagras will retaliate not against CJNG directly, but against the families of known CJNG affiliates continuing a cycle of vengeance that has already claimed thousands of innocent lives.

The violence could spill over into broader civilian life, as it often does. Family members, acquaintances, or even neighbors of those affiliated with “The Clown” may now be at risk. In this brutal world, guilt by association is often enough to warrant death.

Social Media: A Global Stage for Local Terror

What sets the “I Want Water” video apart is not just its cruelty, but the speed at which it spread. Uploaded to various dark web forums and social media platforms, it quickly gained infamy far beyond Michoacán. Memes, reaction videos, and online commentary followed transforming a moment of torture into a viral phenomenon.

This digital spread has opened debates about the ethics of consuming such content. While some argue that viewing these videos raises awareness of cartel violence, others point out that it risks normalizing or even glamorizing torture.

More alarmingly, the viral nature of the content may encourage cartels to continue producing such material knowing that each act of savagery may reach global audiences and further cement their image as untouchable forces of fear.

The Government’s Limited Reach

Despite the growing crisis, the Mexican government has struggled to contain cartel activity in Michoacán. Military deployments and federal police operations have shown mixed results, often facing ambushes, roadblocks, and local resistance.

The absence of strong law enforcement has allowed men like “The Clown” to operate with near-impunity. Local law enforcement is often either outgunned, corrupted, or simply afraid to act. In some regions, cartels function as de facto governments collecting “taxes,” delivering “justice,” and maintaining control through terror.

The execution of the Mexican Ghost Rider and the chilling presence of “The Clown” are more than isolated acts of cruelty they are symptoms of a deeper, systemic collapse in parts of Mexico. As cartels evolve from mere drug traffickers into warlords with media strategies, their methods become more brutal, more symbolic, and more terrifying.

For the residents of Cotija, Aguililla, and broader Michoacán, this video is not just a spectacle it is a warning. And for the world watching from afar, it serves as a brutal reminder that some wars are fought not just with bullets, but with messages written in blood.

World News -Ronnie McNutt Video and Social Media Responsibility

Justin Mohn Video and Incident Posted on YouTube

Russian Lathe Machine Incident Footage Real Video

Robert Godwin and Steve Stephens Video and Caught

Otavio Jordao da Silva Video and Angry Spectators

Finny Da Legend Shooting Video and Livestream on Las Vegas

Tijana Radonjic Parasailing Fall Full Video Footage